[an error occurred while processing this directive]

![[Floris Lambrechts]](../../common/images/Floris_Lambrechts.png)

by Floris Lambrechts

<floris(at)linuxfocus.org>

About the author:

I have been the LinuxFocus/Nederlands main editor for years. I'm

studying 'industrial engineer in electronics' in Leuven, Belgium

and waste my time toying with Linux, PHP, XML and LinuxFocus, while

reading books like those by Stephen Hawking and (at the moment:)

Jef Raskin, 'The Humane Interface'.

Content:

|

Getting to know XML

![[Illustration: xml]](../../common/images/illustration242.png)

Abstract:

This is a pretty short introduction to XML. You will meet Eddy the

meta cat, the XML syntax police, and some DTDs. Don't worry, we'll

explain ;-)

Introduction

In the summer of 2001, some of LinuxFocus's editors came together in

Bordeaux during the LSM. Many

talks and discussions at the LSM's documentation

special-interest-group turned out to have the same subject: XML.

Long (and fun) hours went into explaining what XML exactly is, what

it's good for and how one can use it. In case you're interested,

that is also exactly what this article will try to discuss.

I'd like to thank Egon Willighagen and Jaime Villate for

introducing me to XML. This article is somewhat based on

information in Jaime's articles, which you can find in the links

below.

What is XML

We documentation guys all knew what XML was about, more or less.

After all, it's syntax is very similar to HTML and it's just

another markup language like SGML and (again) HTML, right? Right.

But there is more to it.

XML has some properties that make it a useful data format for

almost anything. It almost seems like it can describe the most

complex things, and yet it remains easy to read for humans, and

easy to parse for programs. How can that be? Let's investigate this

odd language.

Eddy, the meta cat

First of all, XML is a markup language. Documents written

in a markup language contain basically two things: data, and

metadata. If you know what data exactly is, please let me

know, but until then let's talk about the metadata ;). Simply said:

metadata is extra information that adds a context, or a meaning, to

the data itself. A simple example: take the sentence 'My cat is

called Eddy'. A human like you knows that 'cat' is

the name of a species of animal, and 'Eddy' is its name.

Computer programs, however, are not human and don't know all that.

So we use metadata to add meaning to the data (with XML syntax, of

course!):

<sentence>

My <animal>cat</animal>

is called <name>Eddy</name>.

</sentence>

Now even a dumb computer program can tell that 'cat' is a

species, and that 'Eddie' is a name. If we want to produce a

document where all names are printed blue, and all species in red, then XML makes it really simple for us. Just

for the fun of it, this is what we would get:

My cat is called

Eddy.

Now, theoretically, we can put the layout information (the

colors in this case) in a separate file, a so-called stylesheet.

When we do that, we are actually separating the layout information

from the content, something that is considered the Holy Grail of

Web designTM by some. So far we have done nothing

special, adding metadata is what markup languages are designed to

do. So then, what makes XML so special?

The syntax police

First of all, XML has a very strict syntax. For example, in XML

every <tag> must have a closing

</tag>. [ Note: since it's a little

stupid to write <tag></tag>

when there's nothing in between, you can also write <tag /> and save a couple of minutes of your

life, eventually].

Another rule is that you can not 'mix' tags. You have to close the

tags in the reverse order that you opened them. Something like this

in not valid:

<B> Bold text <I>Bold and

italic text </B> italic text </I>

The syntax rules say that you should close the </I> tag before you close </B>

And, be aware, _all_ the elements in an XML document should be

contained in tags (except the two outer tags, of course!). That is

why, in the example above, we have written <sentence> tags around the sentence. Without

them, some of the words in the sentence would not be included

between tags, and that, like so many things, makes the XML syntax

police really mad.

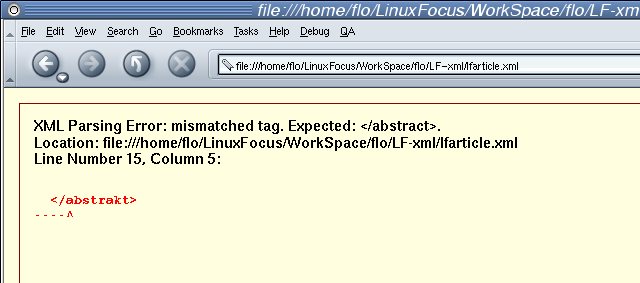

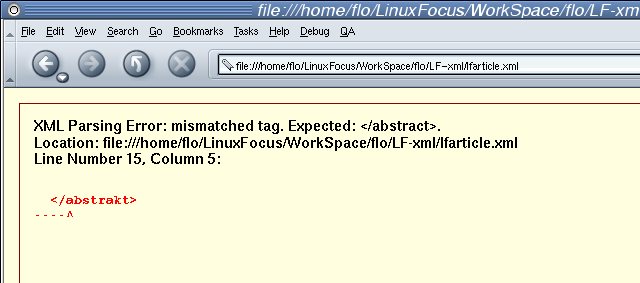

Mozilla's syntax police @work...

But a strong police force sure has it advantages: it brings

order. Since XML follows such strict syntax rules, it is very easy

for programs to read. Also, the data in your XML documents is very

structured, which makes it easy to read and write for humans.

Please note that the 'theoretical' assets of XML are not always

realizable in practice. For example, most current XML parsers are

far from fast, and often really big. So it appears that XML is not

that easy to read for software at all. Let's just say it's

certainly not a good idea to do *everything* in XML, just because

you can. For applications where you need to do a lot of lookups in

a document, or where you have really huge documents, XML is often

not the right choice. But that doesn't mean it's impossible to use

XML for those purposes.

A nice example for the power of XML, but also for it's slowness, is

the fact that you can write databases in it (try that with HTML!

:p). That's exactly what Egon Willighagen has done for the Dutch

LinuxFocus section, his article about that system is available in

the links at the bottom of this page. In this case the flexibility

and extensibility of a homebrew file format were chosen above pure

speed (say, mySQL).

Concerning the strict syntax of XML: if you manage to become good

friends with the syntax checkers, then there may be some ways you

can let the police actually do some of your work. If you want to do

so, you'll have to make clever use of a DTD...

The DTD

In our little 'Eddy the meta-cat' example above, we have

invented our own XML tags. Of course, such a creative act is not

tolerated by the police force! The 'men in blue' want to know what

you are doing, how, when and (if possible) why. Well, no problem,

you can explain everything with the DTD...

A DTD allows you to 'invent' new tags. In fact, it allows you to

invent complete new languages, as long as they follow the XML

syntax.

The DTD, or Document Type Definition, is a

file that contains a description of an XML language. It is actually

a listing of all the possible tags, their possible attributes, and

their possible combinations. The DTD describes what is possible in

your XML language, and what's not. So, when we talk about an 'XML

language', we are actually talking about a specific DTD.

Put the police to work

Sometimes the DTD will force you to do something at a

specific place. For example, the DTD can force you to include a tag

that contains the title of the document. What's so nice about this

is, that there is actually software (e.g. an emacs module) that can

write the required tags automatically.

That way, some parts of your document's structure gets filled in

automatically. Because the syntax is so strict and well-defined,

the DTD can guide you through the process of writing a document.

And when you make mistakes, such as forgetting to place an end tag,

the police will inform you. So in the end, the cops are not that

'mad' at all; where the real-world cops say 'You have the right to

remain silent', the XML police tells you very friendly about a

'Syntax error @ line xx : '... :)

And while the police do all that work for you, of course *you* can

just go on and concentrate on the content.

In the mix

One last great feature of XML is it's ability to use several DTDs

at once. This means you can use several different data types at the

same time in one document.

This 'mixing' is done with xml namespaces. For example, you can

include the Docbook DTD into your .xml document (for the 'dbk'

prefix in this example).

All Docbook's tags are then ready to be used in your document in

this form (let's say there is a Docbook tag <just_a_tag>):

<dbk:just_a_tag> just some words

</dbk:just_a_tag>

Using the namespace system, you can use any tag and any attribute

of any xml DTD. It opens up a world of possibilities, as you can

see in the next chapter...

Available DTDs

Here is a small collection of DTDs that are already (partly) in

use.

- Docbook-XML

Docbook is a language for writing structured documents, e.g.

books and papers. But it's also used for very different tasks.

Docbook is actually an SGML DTD (SGML is a markup standard), but

there is a -popular- XML version of it too. This is one of the

most popular XML DTDs.

- MathML

MathML is the Mathematical Markup Language, which is used to

describe mathematical expressions and formulas. It's a really

neat tool for people in the math world. Chemists on the other

side don't have to be jealous of their colleagues the

mathematicians; for them there is also something like CML, or

Chemical Markup Language. Note that Mozilla 1.0 now has MathML

support by default.

- RDF

RDF is the Resource Description Framework. It's designed to help

encode and re-use metadata; in practice it is often used by

websites to tell other sites which news they are displaying. For

example, the Dutch site linuxdot.nl.linux.org uses

the RDF file of other sites to display their news items. Most

popular news-sites (like e.g. Slashdot) have an RDF file

available so you can copy their news headlines to e.g. a sidebar

on your homepage.

- SOAP

SOAP stands for Simple Object Access Protocol. It's a language

used by processes to communicate with each other (exchange data

and perform remote procedure calls). With SOAP, processes can

communicate remotely with each other, e.g. over a the http

protocol (internet). I think Atif here at LF can tell you more

about it, see the links :-)

- SVG

Scalable Vector Graphics. The trio PNG, JPEG2000 and SVG is

supposed to embody the future of images on the web. PNG will take

the role of GIF (lossless compressed bitmaps with transparency),

and JPEG2000 might someday succeed the .jpg of today (bitmaps

with a configurable degree of lossy compression). SVG is not a

bitmap-based, but a vector-based image format, meaning that

images are not represented by pixels, but by mathematical shapes

(lines, squares,...). SVG also has functions for things like

scripting and animation, so in a way you can compare it with

Macromedia's Flash. You can use JavaScript in .svg files, and

using that JavaScript, you can in turn write .svg code. Pretty

flexible, huh ?

But svg is relatively new; at the moment there is only a

high-quality SVG browser plugin available from Adobe for the

Windows & Mac platforms. Mozilla is working on an embedded

SVG viewer, but that one is not yet completed and you have to

download a specially compiled version of the browser in order to

use it.

NOTE: .svg files can become pretty big, which is why

you'll often encounter .svgz files. These are compressed

versions, using the gzip algorithm.

- XHTML

XHTML is the XML variant of HTML version 4.01. Due to XML's

strict syntax, there are a couple of changes - there are some

things you can do in HTML that are not valid in XHTML. But on the

other hand, a page you write in XHTML is at the same time a valid

HTML page. Note the program HTML tidy can convert your existing

HTML pages to XML.

- The others

Many new file formats use XML, often in combination with .gz or

.zip compression. Just an example: the KOffice file formats are

XML DTD's. This is very useful, because it allows the user to

combine the functionality of different applications in one

document. E.g.: you can write a KWord document, with an embedded

KChart spreadsheet in it.

Links

The W3C, or World Wide Web Consortium

They have info on XML, MathML, CML, RDF, SVG, SOAP, XHTML,

namespaces...

www.w3.org

Some stuff by Jaime Villate (you may need an online translator

to read the first two:)

Introduction to

XML(in Spanish)

How to generate HTML with XML(in Spanish)

LSM-slides

HTML tidy, the program:

www.w3.org/People/Raggett/tidy

Docbook

www.docbook.org

Mozilla.org's SVG project

www.mozilla.org/projects/svg

Relevant LinuxFocus articles:

Using XML and XSLT to

build LinuxFocus.org(/Nederlands)

Making PDF documents with

DocBook

Talkback form for this article

Every article has its own talkback page. On this page you can submit a comment or look at comments from other readers:

2002-04-30, generated by lfparser version 2.28

![[Floris Lambrechts]](../../common/images/Floris_Lambrechts.png)

![[Illustration: xml]](../../common/images/illustration242.png)